- Home

- Lin Carter

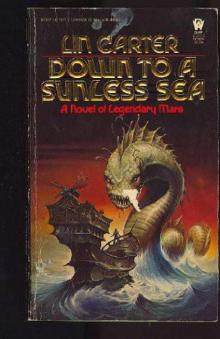

Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea

Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea Read online

The Storm

When Brant saw the sooty smudge on the horizon, he reined in his loper with a muttered curse and sat the saddle, staring with narrowed eyes.

Dust storms are very rare on Mars, where the bitter-cold air is too thin to maintain dust particles for long. But air, however thin, remains air and has its currents.

And that dark, bruise-purple blur on the skyline was a dust storm, all right.

He growled another curse, and felt despair gnaw at his heart. He was a big, hard man with a dark, strong face and eyes as fiery black as Satan’s heart. Not a man to have very often known fear.

Well, he knew it now… .

The thick, thick dust that carpets the dead sea bottoms of Mars is fine as talcum. It seeps into the pores of your skin, it leaks through solid plastic, even through a thermal suit of nioflex. There is no way to keep it out of your eyes, your lungs, your guts. And that is under ordinary conditions … but when ten thousand tons of superfine particles come howling down on you, whipping and whirling on every side… .

It’s not a slow death, true. But it’s not an easy death, either.

He rose in the saddle and looked around, using his UV goggles, for day was dimming toward the sudden nightfall of this far world and it was hard to see for any great distance. Everywhere, save to the south, he saw gaunt-ribbed plains of empty rock, for he was atop one of the stony plateaus that

had been ancient continents once, lush and fertile, lifting sheer from the seething waves of prehistoric seas. It was either that, ride the highline, as they called it, or waste your loper’s strength slogging through the tenacious dust that pulled and sucked like a lake of molasses.

When the oceans dried up and the living things dwindled, the continents had cracked like an apple skin drying in the sun. Some of these fissures were dozens of fathoms deep … but none of them afforded him a safe haven from the hissing storm that was approaching.

Brant had gone riding out from Sun Lake City a month before, angling south across the great stony continent called Ogygis Regio. He wasn’t looking for anything in particular; he wasn’t even prospecting. But there was a corpse back in the city with a knife in its guts, and the handle had his fingerprints all over it. The Colonial Administration cops were a philosophical lot, and another barroom brawl was just another barroom brawl. It would all blow over in time, Brant knew, but for a while it would be healthy not to be around.

Well, when that crawling stain of dark purple spreading across the sky got here, he would be neither healthy nor around. Again, he searched the bleak terrain for a hiding place, but saw nothing. Nothing but … what was that huddle of jumbled rock to the south? He turned up the frequency on his goggles and peered again.

Excitement flared within Brant, for it was a city. The ruins of one, rather. When all this gaunt plateau had been lush with leafage, it had been a proud and princely metropolis, perhaps. Now it was dead as Nineveh and Tyre, although much, much older.

He pulled the reptile’s head around and thumped bootheels in its scaly sides. It voiced a shrill hiss of displeasure, then broke into that clumsy gait for which it was named.

With luck, he might barely reach a place of refuge in the ruins, before the wings of the storm closed around him. Anything would do, a crypt, a cellar, a mausoleum.

Anything was better than the soft, clinging tomb he feared, buried alive beneath tons of hissing cinnamon-colored dust.

He made the walls well before the storm swept down upon him. There was no need to find the gates, for the walls had fallen a million years ago, and lay tumbled about, huge untidy slabs, like a game of dominoes abandoned by the careless children of giants. He rode into streets older than Egypt and past the hollow shells of palaces that were young before the first man-things crept whimpering from the steaming fens under the nodding cycads of a forgotten Dawn.

All of pale golden marble and rose-pink stone was the city built. It had been fair once, very fair. Like an ancient crone who had once been famous for her loveliness, the bones of its lost, faded beauty still showed, here and there.

Forlorn and ruined, it was still a dream of fairness with its pale golden marble and old pink stone, dreaming under the purple sky. And a line from an old, old poem whispered from the depths of his memory���

A rose-red city, half as old as time.

He rode his loper into a square that had been ancient before the cornerstones of the first pyramid were hewn and set in place beside the green Nile, and here he found the first of many mysteries.

They had staked the woman out to die.

They had stripped her mother-naked and tied her wrists and ankles with tight, cruel thongs to pegs driven deep into the crevices between the ancient flagstones.

She was not yet dead, although her tongue protruded, swollen, between parched, cracked lips and black circles of fatigue were drawn around her lustrous eyes.

Nor had her suffering dimmed the bright, fierce spirit of her, for she raised her dust-dark face from the flags to glare at him in silent menace. Does she think I’m going to rape her? thought Brant wryly.

It wasn’t a bad idea, at that, for she was very beautiful, with the long, supple legs of a dancer, a narrow waist, and high, proud, full, yet pointed, breasts.

He dismounted, cast a wary glance behind him at the darkening sky, and strode to where she lay spread-eagled.

He gave her water, just a dribble at first, to moisten her lips and tongue slightly. She sucked greedily at each drop as if her life depended on it, which, of course, it did. Then a little more.

She essayed a question, but her voice was an unintelligible croak. He shook his head, gave her a few drops more. Then he took out his knife and cut the thongs, prying them from the tender flesh of her swollen wrists and feet. Tenderly, he began to chafe the circulation back into her limbs. Like all of the natives, she had the coppery-red skin and russet hair and lambent emerald eyes he was accustomed to. But whereas most of the Martian women straighten their wooly hair into long and lustrous tresses, usually dyed ink-black, she wore her furcap short and trimmed like that of a man. It gave her a piquant, gamine appeal he found stirring.

From the looks of her, she had been here three days, perhaps longer. It was a marvel that she still lived, the copper-red woman with the emerald eyes. But she was of the Low Clans, surely, and they are tough and strong.

Tough, and hard to kill. His lips twisted in a dour grin that bared white teeth. They have to be that way, the Martian natives of the wild nomad clans, for the Colonial Administration has done everything they could have done to ensure they did not survive.

He gave the naked women more water, and she drank it gratefully. But her eyes were still cold and wary, filled with menace, fiery with contempt and hatred. To her he was only a cursed f’yagh, an Outworlder from nearer the sun, come to loot and plunder her dying planet of its last pitiful treasures.

Brant dug into his loose robes for the brandy, but the woman stopped him with a curt nod.

“I am strong enough … see to her, to my ‘sister’ …”

He looked and saw, under a crumbling portico, yet another naked woman staked out to die like the first. And his dark brow scowled with puzzlement: what crime had these women done, to merit such a cruel, slow, lingering death?

He went to tend to the second as he had the first. There was no menace in her doe-soft eyes, only dim bewilderment and stirrings of fear. Where the first woman had been lithe and lean, the second was soft and rounded, a timid little woman to be coddled and cuddled���as for the first, Brant would rather cuddle a sandcat.

By the time he had gotten both women to their feet, the storm was

upon them, shrilling like a thousand demons, sheets of dark red sand hissing between the pillars. Brant loosed the loper, let it precede him into the interior of the nearest building while he half-carried and half-dragged the two women to shelter. The tall one with the dancer’s legs shouldered him aside, to take the smaller one in her arms, hands locked under soft, plump breasts.

“Okay then, do it yourself,” growled Brant under his breath. But he loosened the power gun in its worn holster on his thigh. That one would as lief put a knife between his ribs as look at him, water-sharing or no water-sharing.

They sought refuge in the cellars, which were as bone dry as most of Mars. Crouched in the gloom, they heard the weird, high song of the dust screaming by overhead.

He unlimbered the saddlebags and took out a squat little cooker powered by dialectric accumulators, and began warming up food. It wasn’t much of a meal, beef stew and canned beans, but all three devoured it hungrily, although the women wrinkled up their noses suspiciously at the odd, foreign smell and taste of it.

He gave them brandy mixed with water, got up, took out his sleeping bag and strode to the corner of the cellar that was the farthest from where the two women sat, and made his bed for the night. Then he tended to the loper’s needs, giving it dried plant-fiber cakes in a leather sack and a few plump leaves and stems for the moisture they contained. Like earthly camels, the ungainly reptiles needed little water and that seldom, but they did need some. Replete, the reptile curled up like a huge dog in a corner, and slept.

And then Brant sought his own rest. Greatly daring, he rolled over and turned his back upon the women, leaving them to their own devices.

In a while, the tall one got up to rummage through the loper’s saddlebags. She found loose robes of warm cloth, and

she and her “sister” curled up together, wrapped in the robes against the night’s chill.

Brant lay awake and wary a long time, waiting, but nothing chanced.

After a time, he slept.

His gun had been in his hand all the while.

Above them, the storm-wind shrilled like a flock of banshees.

But after a time, the storm slept, too.

The Women

With dawn he woke to delicious odors and rose to find that the tall woman had arisen before him, and had heated the remnants of last night’s meal, pouring equal portions into three ceramic bowls she had found God-knows-where.

She and her plump “sister” squatted on their heels, wrapped in the clinging robes they had discovered in the saddlebags, wordlessly waiting for him to join them and to share the meagre meal.

It was a gesture of peace, he knew. He flashed them a hard grin and went to sit across from them, squatting as easily as did they. And they ate together, and “shared water.”

That little ritual was very important. There was water-truce between them now, he knew; neither would violate the unspoken truce unless he attempted to harm them, or tried to take them by force.

The ritual done, Brant addressed them, laying his hand upon his hard-muscled chest and speaking his name carefully.

The women frowned slightly at the odd name, but the tall one laid her long-fingered hand between her thrusting breasts and said in the ancient speech, “I am Zuarra; this is my ‘sister,’ Suoli.” Her speech had the tang of the Low Clans in it, he noticed. And again he wondered for what sin they had been staked out by their people to die, but knew better than to offend Custom by daring to ask.

He nodded, finished the last drop of his meal, then rose.

“Best that we get started,” he said gruffly. “We may have to dig ourselves out of here.”

The storm had passed overhead sometime during the night, and the dawn sky was clear. Fine dust squeaked and crunched grittily underfoot as they emerged onto the square and looked about them, grateful to be alive.

While he was saddling the loper, the taller woman approached him.

“Whither do you go, O Brant?” she inquired.

He shrugged good-humoredly. “Nowhere in particular, girl. Where do you want to go? I guess you will not be returning to the camps of your people?” It was really not intended as a question, nor did she take it for one.

“The Moon Hawk nation are our people no longer,” she said without inflection. Then, with a little cold smile that bared sharp teeth in an ugly grimace, she added: “Suoli, my ‘sister,’ says we should go to the city of the f’yagh, there to open our thighs to your kind for bread and meat.”

Brant said nothing, but grinned inwardly. The Earthsider colonist who tried to bed this wench would find a knife between his ribs before he got her thighs apart, he knew. But, after all, what else was there for the two women to do? It is hard enough for a man, even a warrior, to be aoudh���an outcast. It was even harder for a woman.

But he was not going back to the colony at Solis Lacus yet, not for another month, at least, and he said as much. And there was not another Earthsider colony in these southerly parts between here and the Pole.

Zuarra took the news stolidly.

“We will cook for you and clean for you and gather plants for water, and guard you while you sleep,” she said in her husky, deep-throated voice. “But we will not open our thighs for you, neither my ‘sister’ nor myself.”

Brant felt his temper rise at that cold, flat, level statement. He had been too long without a woman, and this one was damnably attractive in a lean, boyish sort of way. But he had his pride, too, and it was as fierce as was Zuarra’s.

“I have not asked you to,” he grated, meeting her eye to eye. “Nor shall I.”

“Then we understand each other, O Brant,” she said

tonelessly. He nodded, and turned his back to finish saddling

the reptile.

The last thing he needed was to have two helpless women on his hands, and women, too, that he could not go to bed with. But he clamped his lips over a growled curse. What could he do? He couldn’t just leave them here to die.

His had been a hard life, had Brant’s, since the courts sent him to Mars, to the penal colony at Trivium Charontis. Since working his way to freedom, he had run guns to the High Clan princes, and sold them liquor and forbidden tobacco, and peddled narcotics to the soft, timid Earthsider clerks and stenographers. He had killed a man more than once; he had cheated at cards; he had stolen.

But he had never treated a woman harshly or unjustly. It was not in him, for a certain rude chivalry flickered in his soul.

He would not betray the best that was within him now.

They rode east, into the Argyre, with the women taking turns in the saddle while he plodded along, leading the loper.

He had no way of knowing it, but he had already taken the first few steps toward the most fantastic adventure any man had ever lived… .

The sky above them was clear, grape-purple, with a few long, thin ribbons of pink cloud-vapor high and to the west. The sun was a small, dull, hard disc of yellow-white fire to the east.

They kept to the high country, to the top of the level rock plateau, with Suoli riding astride the loper, as she was the weakest of the three. Brant and Zuarra strode afoot, alternately leading the reptile by the loop of the reins.

After a time, the loose robe entangling her legs, making her stumble, she swore, removed the garment, and went forward naked. Brant dropped back behind her a little, admiring her long-legged, tireless stride and watching the roll of her firm buttocks as she led the way.

She was damnably desirable, and in the beauty of her nakedness she struck fire in his loins. But he neither said nor did aught to let her know it. He had enough trouble on his hands just then, without aggravating this tawny wildcat of a woman.

After some hours, they came to a deep, narrow ravine in the level tableland, where fat-leaved plants grew. These the women gathered for the pressure-still, while Brant clambered from ledge to ledge, hunting. Erelong, he found a fat, tangerine-colored reptile whose flesh he knew from experience to be edible, and slew it with

a bolt from his power gun, the dial set to needle-beam.

While the women skinned and disemboweled the kill, Brant searched the Colonial Administration Survey charts he carried to seek some sort of haven against the bitter cold of night. They could not be lucky enough to find another dead city, he knew, and this was dangerous country. Predatory reptiles called rock dragons made their lairs in crevices such as these. Customarily, they hunted and fed on the same sort of plump, harmless lizards as the one Brant had just slain; but they were not averse to the taste of manflesh, either.

They rested for a time, and Brant fed more plant fiber to the loper, while the women cooked the steaks and chops they had trimmed from the carcass of the lizard in the portable cooker. That night they would feast, he knew.

He stood and watched them as they worked together, squatting on their heels, hands moving with practiced skill, and he wondered what their story might be.

It had not been for naught that two such women, young, each attractive in different ways, both of child-bearing age, had been staked out to die a slow, lingering death from thirst and starvation, he knew.

But he also knew better than to ask.

They rode on, as the distant sun declined in the west and the sky darkened to deep purple. Brant had found a haven on the Survey map, a mound of broken rocks believed to have been the burial mound of an ancient king, since it was obviously of artificial origin. When they reached it by late afternoon or early evening, he unpacked the small tents of heat-retaining plastic he had brought along for himself and the loper in case they rode into the polar wastes. One of these he set up for himself, the other for the women. The loper he tethered to a boulder, and fed the creature on the remainder of the fibre.

They shared the meal, seated on opposite sides of the fire. It was not wood they burned, of course, since Mars has nothing in the way of trees, but a colorless, aromatic oil in a flat pan. This fluid provided both warmth and light.

The fresh-cooked meat tasted good, after a diet of canned goods. The steaks were succulent and juicy and broiled to perfection. But when he complimented Zuarra on her culinary skills, she shot him a level, contemptuous glance and her mouth twisted sardonically, saying nothing. It was as if, by praising her skills as a woman, he had somehow insulted her.

Zanthodon

Zanthodon Thongor in the City of Magicians

Thongor in the City of Magicians Thongor at the End of Time

Thongor at the End of Time The Valley Where Time Stood Still

The Valley Where Time Stood Still Journey To The Underground World

Journey To The Underground World Darya of The Bronze Age

Darya of The Bronze Age Eric of Zanthodon

Eric of Zanthodon Hurok Of The Stone Age

Hurok Of The Stone Age Tower Of The Medusa

Tower Of The Medusa Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus

Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus The Zanthodon MEGAPACK ™: The Complete 5-Book Series

The Zanthodon MEGAPACK ™: The Complete 5-Book Series The Quest of Kadji

The Quest of Kadji Lin Carter - The Man Who Loved Mars

Lin Carter - The Man Who Loved Mars Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria

Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria The Nemesis of Evil

The Nemesis of Evil H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos

H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea

Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea Horror Wears Blue

Horror Wears Blue Invisible Death

Invisible Death Lin Carter - The City Outside the World

Lin Carter - The City Outside the World The Volcano Ogre

The Volcano Ogre The Man Who Loved Mars

The Man Who Loved Mars