- Home

- Lin Carter

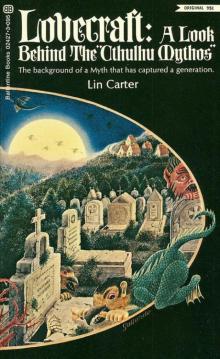

H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos

H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos Read online

THE CTHULHU MYTHOS...

What arcane horrors, dimlit landscapes, nauseating monstrosities are conjured up by these words! The creation of H. P. Lovecraft, the Mythos has fired the imaginations of generations of readers—and of writers, giving rise to a fresh host of stories (some of which you will find in THE SPAWN OF CTHULHU, edited by Lin Carter) by innumerable authors who have added immeasurably to the original concept.

Who was Lovecraft? What was he like? What were his sources, and did he believe in any part of the grisly worlds he created in the Mythos?

In clear, affectionately objective prose, Lin Carter examines the Myth, and the man behind the Myth.

Lovecraft: A Look Behind the “Cthulhu Mythos”

Lin Carter

BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK

Copyright © 1972 by Lin Carter

First Printing: February, 1972

Cover art by Gervasio Gallardo

(Version 2.0)

Introduction: The Shadow Over Providence

1. The Visitor from Outside

2. Intimations of R’lyeh

3. The Thing on the Newsstand

4. The Horrors of Red Hook

5. The Coming of Cthulhu

6. Acolytes of the Black Circle

7. The Gathering of the Shadows

8. The Spawn of the Old Ones

9. The Elder Gods

10. Invaders from Yesterday5

11. The Last Incantation

12. Beyond the Tomb

13. The House in the Pines

14. End of an Epoch

15. The Last Disciple

Appendix: A Complete Bibliography of the Mythos

A word of thanks

In researching and writing this book, I have called on many friends and colleagues for advice and assistance. It seems only proper to thank them here for their many kindnesses. I am most grateful to Robert A. W. Lowndes and Frank Belknap Long for sending me copies of certain rare and obscure items in the Mythos, the texts of which I had else found it all but impossible to obtain; to L. Sprague de Camp, for lending me copies of certain unpublished letters written by Clark Ashton Smith to Lovecraft, to Donald A. Wollheim, for sharing with me some of his memories of Lovecraft; and to August Derleth, Robert Bloch, and Frank Belknap Long, for answering many questions and helping to resolve several difficult problems of Lovecraftian lore.

Above all, I am particularly grateful for the help, advice, encouragement and assistance of August Derleth, who died while this book was being written. Although his own work schedule was crowded, he was never too busy to answer an urgent telephone call for his opinion or data, or reply to a lengthy letterful of detailed questions. I particularly appreciate his kindness in supplying me with information on yet-unpublished stories of his own, and lending me a xerox copy of a newly-discovered Mythos story by Robert E. Howard, and in reading and commenting critically on the first 103 manuscript pages of this book. He did not live to read the remainder of this book, but I hope he would have approved of it.

In a rather large part, it is due to the interest and the generosity of such men as these that this book is as complete, as authoritative, and as accurate as it is. Without their help it would have been a weaker book by far.

This book is a history of the growth of the so- called Cthulhu Mythos, and it does not purport to be a biography of H. P. Lovecraft. It reflects my own interest and enthusiasm in that curious and delightful sub-literature, and is, therefore, rather subjective. Many of the value judgments expressed herein are a matter of personal opinion. August Derleth, commenting on the first half of the manuscript, took me severely to task for the predominance of personal opinion in what he felt should be an impersonal work of scholarship. Those who desire impersonality in their literary histories must, I fear, seek elsewhere for it. For better or for worse, this book has evolved out of my personal involvement in the Mythos and out of my own fascination for the marvelous stories therein, which were among the chief delights of my early reading. So —caveat emptor; and read on!

—Lin Carter

Introduction:The Shadow Over Providence

Our century has seen some of the finest craftsmen who ever worked in the tradition of the weird tale. My own list would begin with Arthur Machen and M. R. James, and would contain such names as Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, and perhaps Robert W. Chambers. But each connoisseur will have his own particular favorites, and another enthusiast might well select A. E. Coppard, Saki, Walter de la Mare or others to head his own list.

The fame, artistry and renown of these writers assumed, it is all the more remarkable that, of them all, probably the best known, the most popular, and certainly the most widely published and most frequently anthologized writer of weird fiction in this century has been an eccentric recluse named H. P. Lovecraft, a pulp magazine writer who died in relative obscurity in Providence, Rhode Island, some thirty-four years ago, and whose posthumous fame has eclipsed that of every other weird-fiction writer since Edgar Allan Poe.

The extent of Lovecraft’s success becomes all the more amazing the deeper you look into it. Beyond the enthusiastic acclaim of the readership of such fiction magazines as Weird Tales, Lovecraft never achieved a large general readership or any real recognition by the literary establishment in his entire career. Not only did he never write a best-seller like Rosemary’s Baby, to choose a recent example, but, outside of a few anthology appearances, hardly anything of his achieved the dignity of hardcovers at all; indeed, only two books of his were published in his lifetime, and these were but slender efforts, privately printed, of which only a few hundred copies were circulated.

Today, thirty-four years after his death at the early age of 47, virtually every word Lovecraft ever set on paper is in print. Whole volumes of his verse, essays, and letters have been published. As for his fiction, everything is in print —his mature work, juvenilia, unfinished fragments, collaborations, revisions, and even his rough notes and commonplace book. The complete Lovecraft oeuvre is in print in hardcover and paperback not only in this country, but in England as well.

His work has been translated to virtually every medium, including comic books. It has been read or dramatized on radio, television, and even on phonograph records. At least four or five movies have been filmed from his stories, and more are in the works. His fiction has appeared in several foreign countries and in many languages, including Portuguese, German and Polish. Pirated Lovecraftiana has been printed in some Iron Curtain countries, such as Yugoslavia.

Lovecraft has won a most extraordinary following among European intellectuals and members of the avant-garde (the two terms not always being synonymous). Particularly in France, Italy, and Spain, a number of translations—reportedly very good ones—have been made. Marc Slonim, who writes the “European Notebook” feature for The New York Times Book Review, discussed this extraordinary literary phenomenon in one of his 1970 articles. He points out that not; only are these translations “widely read in Paris, Rome and Madrid, but Lovecraft is also hailed by the leading critics as superior to Poe. The Spanish essayist Jose Luis Garcia recently included Lovecraft in a list of 10 best writers of the world, and the French sophisticated periodical L’Herne dedicated a special large issue to {his ‘greatest American master of supernatural literature.’”

Also in 1970, Lovecraft virtually dominated a mammoth, 700-page dictionary of “the marvelous, the erotic the surrealistic, the unusual”—a book called Arcana, published by the Milanese firm of Sugar and hailed as a literary event by Italian critics. Fifty writers contributed to the-compilation, and the article by Sebastiano Fusco, on H. P. Lovecraft, was the longest in the entire work.

>

The posthumous success of Lovecraft, and his triumph over far more gifted writers in the genre, also comes as a surprise when you take a clear look at his work. He has no ability at all for creating character, or for writing dialogue. His prose is stilted, artificial, affected. It is also very overwritten, verbose, and swimming in adjectives. His plotting is frequently mechanical, and his major stylistic device, which becomes tiresome, is the simple trick of withholding the final revelation until the terminal sentence—and then printing it in italics, presumably for maximum shock value.

In all fairness, let me point out, however, that none of the remarks in the foregoing paragraph really means much. Thomas Wolfe was also verbose and frequently employed a plethora of adjectives—none of which keeps him from being a great American novelist. Faulkner wrote an affected, artificial style, at least part of the time, and one of his stylistic tricks—even more annoying than most of Lovecraft’s—was the concocting of elaborate sentences running to a hundred words and more. And as for character, dialogue, and even plot, many respected modem writers totally dispense win these, with no visible damage to their reputations. 1*

The secret of Lovecraft’s success, and perhaps that of his popularity as well, lies in innovation. Where Coppard, James, and many of the other perhaps more gifted macabre writers of the century were, in the main, content to rework the familiar themes of ghosts, were-wolves, vampires, hauntings, and so on, Lovecraft struck boldly into fresh new paths. Lovecraft seems to have realized that any dreary hack could raise a crop of gooseflesh with a tale of black-cloaked vampires set in dim Transylvania, or a story of shaggy, flame-eyed werewolves prowling the dark forests of the Rhine, These things had been done, and they had been done to death. Lovecraft did not have a particularly high estimate of his own fiction, but he refused to dd over again what others had already accomplished.

“I refuse to follow the mechanical conventions of popular fiction or to fill my tales with stock characters and situations,” he once wrote in a letter to a friend. “But [I] insist on reproducing real moods and impressions in the best way I can command.”

Since anyone could turn out horror tales in the conventional settings, he seems to have set himself the task of making horror convincing in the here and now. Time and time again, in the pages that follow, we shall see Lovecraft taking the most unpromising of locales —sleepy old Colonial New England seaports, the verdant hills of Vermont in the 1930’s, even the brick labyrinths of modem Brooklyn—and striving to rouse the reader to shuddersome thrills.

Lovecraft, whatever his failings as a human being and even as a writer, possessed a first-class intelligence —cold, analytical, shrewd—when applied to the study of weird fiction. His scrutiny of the entire range of supernatural horror in literature, which in time resulted in the brilliant monograph of that title, exemplifies his critical standards. Elsewhere on the subject of “how to pull the trick off,” he wrote:

To make a fictional marvel wear the momentary aspect of exciting fact, we must give it the most elaborate possible approach—building it up insidiously and gradually out of apparently realistic material, realistically handled. The time is past when adults can accept marvelous conditions for granted. Every energy must be bent toward the weaving of a frame of mind which shall make the story’s single departure from nature seem credible— and in the weaving of this mood the utmost subtlety and verisimilitude are required. In every detail except the chosen marvel, the story should be accurately true to nature. The keynote should be that of scientific exposition—since that is the normal way of presenting a ‘fact’ new to existing knowledge—and should not change as the story gradually slides off from the possible into the impossible.

This notion of utilizing something akin to scientific exposition in building a tale of supernatural horror was not precisely new to the genre. Bulwer-Lytton had attempted something of that nature in his fine tale, The House and the Brain; even Frankenstein employs surgical and electrical information to build credibility. But Lovecraft carried the idea to its logical extremes, and the result was a new form of supernatural horror in fiction.

Strictly speaking, Lovecraft’s best work should not be described as supernatural at all: stock spooks, clanking chains, ancestral curses, and familiar monstrosities seldom enter his tales at all. In fact, his essential themes are more closely akin to science fiction—so closely that it might well be said that he indeed wrote science fiction, although it is the science fiction of horror and thus, technically, a new genre in its own right. In his letters he frequently remarked: “All my stories, unconnected as they may be, are based on the fundamental lore or legend that this world was inhabited at one time by another race who, in practicing black magic, lost their foothold and were expelled, yet live on outside ever ready to take possession of this earth again.” I submit that, excepting only the bit about “black magic,” this is essentially a science fictional concept.

In his fiction, Lovecraft developed this theme with stories that were very much more explicit. In the ages before the evolution of man on this planet (his stories reiterate), the earth was visited and colonized, conquered and ruled, by successive waves of completely alien beings of superior intelligence and awesome longevity and other powers, who came down to this planet from other planets or distant stars or beyond the three-dimensional universe, the space/time plenum itself.'

Such a theme, found in the pages of E. E. Smith’s epic “Lensmen” series, or Olaf Stapledon’s titanic novel, Star Maker, would be accepted as science fiction without qualm or reservation. Taken in the mood, the style, the context of tales of horror, it is shocking and new. It is largely in this respect that we consider Lovecraft as an innovative writer who brought something thoroughly new to the genre of the macabre.

For, as he began to evolve his Mythos stories, we learn that Cthulhu and Tsathoggua and the other members of the Lovecraftian pantheon are not really gods, not even demons—they are nonhuman extraterrestrial invaders. One wave of this invasion came from Yuggoth (Lovecraft’s name for Pluto, the ninth and outermost known planet of our system), as revealed in a story called The Whisperer in Darkness; another race gained possession of the earth in remote geological epochs and came from a planet called Yith (as The Shadow Out of Time tells); and as Lovecraft’s story-series now stands, the powerful beings who were long ago expelled from this world are not far away, and many of them lurk on the worlds of such nearby stars as Aldebaran, Fomalhaut, and so on, while their adversaries dwell on a planet of the star Betelgeuze Clearly these concepts are those of science fiction, not supernatural horror.

While most of Lovecraft’s fiction is worth the reading, and much of it has permanence, his major fame rests on those stories which we call “the Cthulhu Mythos.” Oddly enough, while Lovecraft wrote about fifty-three stories (not including prose poems, juvenilia, fragments, revisions or posthumous collaborations), only a dozen or so belong to the Cthulhu Mythos. Indeed, many of his most famous stories have nothing at all to do with the Mythos, tales such as The Outsider, The Rats in the Walls, Pickman’s Model, The Horror at Red Hook, and many more.

In this book I propose to explore the Cthulhu Mythos what it is, how it evolved, why it is so brilliant and successful an achievement. For the Mythos has other claims to fame beyond rendering internationally famous the obscure pulp-magazine writer who first conceived it. It is as remarkable a literary phenomenon as this century has seen. And this seems as good a place as any to explain precisely what we mean by this term “the Cthulhu Mythos.” In the first place, the word mythos does not exactly belong to the English language. Neither is it a neologism, a coined word. Mythos is Greek and can mean “myth, fable, tale, talk speech,” or so my Webster’s Collegiate informs me.

In discussing a certain body of interconnected stories by H. P. Lovecraft and other writers, we use the word in a special sense, which might be defined as: “a corpus of fictitious narratives which share as their common background a system of invented lore.” Lovecraft certainly did

not invent the term, and he never once used it in print, not even in his voluminous correspondence. (In fact, he seems to have been completely unaware that certain of his stories could be singled out as belonging to the Cthulhu sequence: As far as he was concerned, all of his work was interconnected.)

The term came into use among Lovecraft’s correspondents as a convenient label. No one today seems to remember who used it first. But it was most likely August Derleth who first used the term in print; Derleth himself thought it was first used in his biographical/critical monograph, H.P.L.: A Memoir, published by Ben Abramson in New York in 1945. But my researches have uncovered an earlier use of the word “mythos” to describe the story sequence, and the actual phrase “the Cthulhu Mythology” used in the same manner, in the Derleth-Wandrei introduction to The Outsider and Others, which was published in 1939.

Perhaps the most unique thing about the Mythos is the fact that it spread beyond Lovecraft himself. Other writers became caught up in it, wrote stories based upon it, extended and elaborated and developed the background lore which Lovecraft invented. At first, it was only some of Lovecraft’s closest friends and correspondents who wrote new stories in his Mythos—writers like Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, Frank Belknap Long, Robert Bloch, August Derleth. But before long, writers like Henry Kuttner, Gardner Fox, Hugh Cave, Manly Wade Wellman, Robert W. Lowndes, Henry Hasse, and Robert Johnson—who had little to do with Lovecraft, in the main—began contributing stories and poems which have been described as belonging to, or bordering upon, his Mythos. And today,; writers who never knew him and in some cases were not even born until after his death, are writing new chapters in the history of the Cthulhu Mythos: Colin Wilson, J. Ramsey Campbell, and even myself.

Lovecraft left twelve stories in the Mythos. August Derleth alone has by now written seventeen, not counting his posthumous “collaborations” with Lovecraft. 2*

Zanthodon

Zanthodon Thongor in the City of Magicians

Thongor in the City of Magicians Thongor at the End of Time

Thongor at the End of Time The Valley Where Time Stood Still

The Valley Where Time Stood Still Journey To The Underground World

Journey To The Underground World Darya of The Bronze Age

Darya of The Bronze Age Eric of Zanthodon

Eric of Zanthodon Hurok Of The Stone Age

Hurok Of The Stone Age Tower Of The Medusa

Tower Of The Medusa Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus

Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus The Zanthodon MEGAPACK ™: The Complete 5-Book Series

The Zanthodon MEGAPACK ™: The Complete 5-Book Series The Quest of Kadji

The Quest of Kadji Lin Carter - The Man Who Loved Mars

Lin Carter - The Man Who Loved Mars Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria

Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria The Nemesis of Evil

The Nemesis of Evil H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos

H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea

Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea Horror Wears Blue

Horror Wears Blue Invisible Death

Invisible Death Lin Carter - The City Outside the World

Lin Carter - The City Outside the World The Volcano Ogre

The Volcano Ogre The Man Who Loved Mars

The Man Who Loved Mars