- Home

- Lin Carter

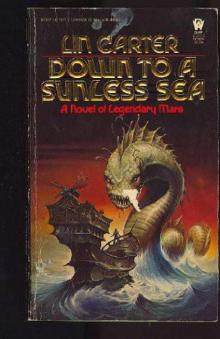

Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea Page 5

Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea Read online

Page 5

He paused, rubbing his jowls.

“On the other hand,” he mused thoughtfully, “that might not be a bad idea. It’ll be to their disadvantage to fight us in the dark, because it would be next to impossible to climb down the cliffs by night. And if they fire on us, we can aim at the flare of their guns. There’s plenty of fallen rocks and boulders around here for us to use as shields against their weapons, and we can keep moving from spot to spot between shots, so they’ll have a hellova problem figuring out where we are at any given time.”

Harbin thought it over, and agreed it looked like the best course of action open to them. ���

“They won’t dare try to get their lopers down the cliffs in the dark, so don’t you think it likely���unless they decide to fire on us after all���that once they know we’re moving out, they’ll ride along the ridgeline, hoping to keep up with us?”

Brant grinned. “They’ll have a hard time figuring which direction we’re going, north or south. So they’ll have to split up, two of ‘em going one way, the rest in the other direction.

If nothing else, it’ll cut their numbers in half and double our chances of winning, if it comes to a fight!”

They talked the plan over, looking for loopholes that hadn’t yet occurred to them.

They found none. It would be touch and go, but the only alternatives to taking that risk looked even riskier.

“So when you suggest we make our move?” inquired Harbin.

Brant grinned wolfishly.

“Right now,” he growled.

The Flight

While the older scientist went to order Agila to pack their gear as unobtrusively as possible, Brant sauntered casually over to the other tents to inform the women of this decision.

Zuarra listened without comment, and nodded grim agreement. She did not question the urgency of the problem, neither did she bother to remark on the risk and danger involved in flight.

Suoli, of course, was timid and reluctant, and needed more reassurance than Brant felt inclined to give.

“Listen,” he said roughly, “I can’t make any guarantees! Sure, we’re taking a big chance, but we’re already in trouble and this looks like the best, maybe the only, way out.”

“But to leave the tents!” the little woman wailed, wringing her soft plump hands. “In the night we will freeze���!”

“So we bundle together for warmth, or look for a cave where we can set up one of the heaters. We don’t have much choice in the matter, don’t you understand?”

Zuarra spoke up. “Is it that you intend abandoning your f’yagha energy barrier, when we ride out?” she asked. Brant nodded somberly.

“Too much of a problem dismantling it,” he pointed out. “Too much chance of them seeing us at it, and realizing what we’re going to do.”

“Then wherever we make camp, we will be in danger of beasts,” said Zuarra.

Brant shrugged impatiently.

“So we’ll take turns standing guard!” he growled. “C’mon,

we’re wasting time���pack your stuff. Since we’re all going to have to ride, we can’t load down the lopers. Bring bedding, all the food, and the pressure-still. Leave everything else.”

With those curt words, he strode out of the tent to pack his own gear.

Thirty minutes later they were riding across the sands.

The lopers hadn’t had much work to do recently, and were fresh and well-rested. Doubling up in the saddle was uncomfortable, but there was no alternative. If one or another of them had to travel on foot, the pace of their flight would be slowed.

Suoli cast a wistful backward glance at the dim lights in the warm tents, and began sobbing breathlessly to herself. Save for her muffled weeping, they rode in silence.

It was Brant’s plan to strike out at angles from the cliffwall, and ride some considerable distance into the dustlands. This would make it exceedingly difficult for the watchers on the ridge to spot them, for the moaning winds of Mars had carved the fine, dustlike powder into rolling dunes taller than a grown man.

When they had gone far enough to his liking, they angled directly south and followed the curving line of the now-distant cliffs.

As far as they could tell, the unknown watchers had not discovered their quarry to be in flight. Probably (grinned Brant sourly to himself) they were huddled in uncomfortable slumber on the cold rock far above, envying those in the encampment below, whom they assumed sleeping cozily in the insulated tents.

Well, come morning, they were in for a surprise.

Brant was almost sorry that the watchers had not discovered their plan and begun firing, for it would be a vast relief to know just what the watchers intended. However, the ink-black darkness had concealed their furtive departure from the watchful eyes above and it did not seem likely that their absence would be discovered before morning.

There was one problem which bothered him and made him a trifle uneasy. And that was, quite simply, that in order to leave the encampment they had been forced to switch off the power fence. There was no alternative to this, for the lopers would have suffered from the energy-laden wires when they rode over them as much as would beasts of prey, for whom the energy fence was designed. But if a predator should choose to enter the camp during the night, to rip open the tents in search of food, surely the rumpus would attract the attention of the watchers, and their flight would be known.

Brant shrugged the problem aside. “The hell with it,” he grumbled to himself. “You can’t take every damn precaution��� and maybe our luck will hold.”

By this time they had put several miles between them and the abandoned camp, and the lopers were weary of laboring through the talcum-fine dust. So Brant headed in to the shelter of the cliffs, where rock outcroppings and pulverized shale would give the beasts easier footing, and enable them to make better time.

It was his intention to ride all night long, and then, when morning came, to hole up somewhere, seeking shelter in the side of the cliffs, where caves and crevices could easily be found. He just hoped that these wouldn’t already be affording shelter to rock dragons or something even bigger, more powerful and more dangerous. But, as he’d just decided, you have to take some risks.

Zuarra was sharing the saddle with him, as she disdained to ride with Agila. For all the danger of their precipitous night ride, and all the various hazards and problems he had on his mind, Brant could not help feeling uncomfortably aware of the proximity of her body to his.

Her hair held a faint trace of perfume���bitter, musky, a dry, spicelike scent that reminded him vaguely of cinnamon.

Her arms were tightly wound about his waist, for she was riding behind him so that he could more easily handle the reins. So close was her embrace, that even through his clothing he could feel the soft pressure of her firm breasts nuzzling into his back.

He tried not to notice that her smooth thigh was pressed against his leg, and that her warm breath panted against his nape. But Brant was only a man, not a priest or a saint, and the warm closeness of their bodies aroused hungers within him, as did the delicious fragrance of her hair.

Muttering an uncomfortable curse, he moved his big shoulders restively, trying to turn his attention to other matters.

It is doubtful whether Zuarra could have understood his words, for they were in English. But women possess certain instincts, and in the windy dark she smiled a slow little smile to herself, understanding the cause of his irritable agitation.

The night seemed endless, and as they swayed in the saddle to the rhythm of the beast’s awkward gait, they found themselves being lulled into sleep. Brant almost fell from the saddle at one point, but Zuarra’s grasp restrained him, and he straightened, stiffening his back, forcing sleepiness from his mind by an act of will.

The lopers themselves were beginning to founder by this time, for the beasts were unaccustomed to being driven for so long at their best pace. Eventually, and with reluctance, Brant had to give the sig

nal to slow down and let the beasts canter at an easier pace, to conserve their vigor.

Dawn took them all by surprise. On this harsh desert world, where the air is incredibly thin, sunrise does not advertise its coming by the slow brightening of light, as it does on Earth, with its thicker, more humid atmosphere. No, dawn is like a vast, silent explosion, which comes upon you with no advance warnings.

One moment they were riding through pitch-black gloom. And, in the next instant of time, daylight flooded the sky and they blinked sleepy eyes against the unexpected brilliance.

Brant pulled up and let Zuarra dismount. Then he got down from the saddle himself, stretching weary legs with a jaw-cracking yawn.

“We’ll take a brief rest stop here,” he advised the others. After a long night spent in the saddle, they were all thankful for an opportunity to relieve their bladders.

Brant and Harbin scanned the ridgeline narrowly, through powerful binoculars, but nowhere could they discern the slightest sign of the unknown watchers. That was one problem off Brant’s mind, at least.

“How far do you think we traveled, Doc?” inquired Brant, wetting his lips with a drink from his canteen. The scientist pursed his lips and hazarded a guess.

Brant grunted. “Better than I could have hoped,” he said. “Well, we’re all worn out, and the lopers are in bad shape. What say we find a place to hole up and get some shut-eye?”

“I could use some,” admitted Harbin with a rueful grin. “Not as young as I used to be… .”

Brant chuckled at that. “You’re made out of whipcord and steel wire, and you know it,” he quipped. “Matter of fact, you look like you’re in better shape than I am.”

This part of the shoreline of the prehistoric continent was grooved and worn into deep gullies, and it didn’t take the travelers very long to find a snug cave. Fortunately, although the crusted droppings suggested it had once served as a rock dragon’s lair, the beast was no longer in residence, and had not been for many years.

The women unrolled the bedding and Harbin asked the younger man as to the wisdom of mounting guard.

Brant stifled another huge yawn, and shook his head blearily,

“Naw, I don’t think so. They’re just now realizing we skipped out last night, and have no way of knowing which way we rode, or how far we went. It’ll be quite a while before they catch up to us, that is, if they bother with pursuit. And that shale we were riding over most of the night won’t show tracks.”

They went to bed and almost instantly fell asleep.

10

The Riddle

Bone-weary as they all were, it was well into the afternoon before any of them awoke.

Brant stretched tired muscles and yawned a jaw-cracking yawn. Then he got up and went out of the narrow cave to relieve himself. He found Harbin already up and dressed.

“I figured you’d still be snoozing,” the big Earthsider grunted. The older man smiled ruefully.

“Old bones don’t rest easy,” Harbin admitted. “People of my age don’t need that much sleep, you know. After all, the Big Sleep is nearer for us than for you young folks.”

Brant grimaced and spat. “Hell, Doc, you’ll see me in my grave, more than likely. Anybody else up?”

Will Harbin shook his head briefly. Stepping away from the cliffwall, Brant scanned the ridgeline with slow and careful gaze.

“Any signs of company?” he inquired.

Harbin shook his head again. “None that I can discern,” he said. “But I hardly suppose that they will be on our track this quickly.”

“Let’s hope not, anyway,” Brant growled. “Another ride like the one we had last night will about do me in!”

Agila emerged from the mouth of the cave shortly thereafter. He ignored Brant as best he might, greeting his employer briefly. Before long, the delicious smell of food being cooked was on the air. Brant sniffed hungrily.

“Soup’s on, I guess. That means the women must be up.”

They broke their fast ravenously, and seldom had hot food tasted better to any of the travelers.

Later on, having fed the lopers, Brant saddled his beast and rode out into the midst of the dunes. Climbing to the top of the tallest one he could find easily, he spent a long time carefully searching the ridgeline with his binoculars. Eventually, finding no slightest sign of their pursuers, he remounted his steed and rode back to the cave, reporting his discovery, or lack of any discovery, to the old scientist.

“Thing is, do we hole up here or keep goin’?” Brant concluded.

“I thought you were the leader of this miniature expedition,” Harbin remarked lightly.

The other shrugged. “Doesn’t matter who’s boss. You’ve got the brains and all the know-how; I got the muscle and the wilderness experience. So what d’you think? Stay, or keep movin’?”

Harbin chewed it over thoughtfully. Finally, he said:

“Our friends will have to split into two groups, one riding north and the other heading south, since they have no way of knowing in which direction we went. Just as you surmised yesterday. And, that is, if they are still tracking us.”

“So?”

“So, even if they come this way, and are still riding the high country, they’ll have no chance of seeing us, providing that we keep to the cave.”

Brant shook his head. “Wrong, Doc. What if they have a pack of hunters?”

Hunters were small, fleet domesticated reptiles used by the Martian natives for much the same purpose as Earthsiders use hunting dogs. They possessed a remarkable sense of smell, and could easily have detected the odors of cooking food or fresh droppings from the lopers, even from the ridgeline.

Harbin scratched his nose. “I didn’t see any hunters before,” he said. Brant shrugged.

“Neither did I. But that doesn’t mean they don’t have ‘em. If I gotta gamble my life, I’d like it to be on a sure thing.”

“So you think we should keep moving, eh?”

Brant looked stubborn. “Goes against my grain to run from a fight,” he admitted heavily. “But they outnumber us and probably are better armed. We got a good head start on them right now, and it might be smart to hang onto that advantage.”

“We simply can’t keep running forever,” Harbin observed shrewdly, “and I, for one, would like to be sure they are still after us, before I continue this flight from a trouble that may, after all, no longer be there.”

“Not bad thinking, 1 guess,” nodded Brant. “Besides, the lopers are still tired from that all-night ride. Let’s hang around here for a while more, keeping a sentinel posted out on the dunes. We can take shifts. And there’s something else … ?”

“Which is?” prompted the scientist.

Brant looked at him squarely.

“I want to find out why they’re after us, whoever the hell they are. Any ideas?”

“None,” said Harbin. Brant continued looking at him.

“Let’s be square, Doc,” he suggested. “I got some cops on my tail ‘cause of a fight in a barroom back in Sun Lake City. I know it isn’t cops we saw watching us from the high country. But outside of that, I’m clean. Oh, sure, you can’t live a life like mine without making enemies, any more than you can make an omelet without cracking eggs. But there’s just nobody that wants me bad enough to chase me into this part of the world. How about you?”

Harbin told him frankly that he was open and above board, and the sincerity in his voice was enough to convince Brant.

“But what about the two women?” the scientist asked. Brant made a negative gesture. Then he told Harbin how he had encountered the two staked out to die, and had rescued them. He concluded:

“Being outlawed and left to either die or fend for themselves on their own is punishment enough for their nation,” he said. “I know the People well enough to know that.”

“So do I,” said the scientist. “That only leaves… .”

“Agila,” growled Brant. “How much d’you know about him, anyway?”

/> “Not very much,” Harbin admitted. “Only what he told me, which was cursory. He’s an outcast, too, like the two women, but it might be that he is not exactly as innocent of wrongdoing as he wanted me to think at the time.”

“Let’s both keep our eyes on him, then,” suggested Brant.

They agreed.

Later that evening, Brant went out among the dunes to relieve Zuarra from sentry duty.

“Have you sighted anything?” he asked. “On the ridgeline or anywhere else?”

“Nothing, O Brant,” she replied.

“Good!” he grunted. Then he mentioned briefly the matters he and the older man had discussed concerning Agila. And he asked her if she had noticed anything at all peculiar or out of the ordinary in the man’s behavior.”

“That one!” the woman sniffed contemptuously. “Zuarra has as little to do with the lean wolf as she may manage.”

“You’ve never talked, then?” he inquired.

“As little as possible���since that night when he would lay unwanted hands upon Zuarra, and Brant felled him with a blow of his fist. Besides,” she added stiffly, “that one now spends as much time as he can find in whispered converse with Suoli.”

Brant suppressed a smile. All women are given to jealousy, he thought cynically to himself. Even those that eschew the embrace of men and choose their own sex for solace.

He began the slow, laborious climbing of the dune to its crest, wherefrom a clearer view of the surrounding country could be had. But before returning to their encampment, Zuarra turned to speak to him again. A sudden thought had struck her.

“Yes?” he inquired.

“It may perchance mean nothing at all, O Brant,” the woman said hesitantly. “But Zuarra has noticed, of nights, before he seeks his pallet, the lean wolf removes something from his baggage, and sleeps with it cradled against his breast. It may very well have naught to do with our present predicament, but Zuarra wonders if Brant has noticed this puzzling act of Agila.” ���

He shook his head. “No, I haven’t. And it may, after all, mean nothing, as you suggest. Or it may be the answer to the mystery of why the unknown strangers are on our trail … of what shape is the thing you speak of?”

Zanthodon

Zanthodon Thongor in the City of Magicians

Thongor in the City of Magicians Thongor at the End of Time

Thongor at the End of Time The Valley Where Time Stood Still

The Valley Where Time Stood Still Journey To The Underground World

Journey To The Underground World Darya of The Bronze Age

Darya of The Bronze Age Eric of Zanthodon

Eric of Zanthodon Hurok Of The Stone Age

Hurok Of The Stone Age Tower Of The Medusa

Tower Of The Medusa Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus

Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus The Zanthodon MEGAPACK ™: The Complete 5-Book Series

The Zanthodon MEGAPACK ™: The Complete 5-Book Series The Quest of Kadji

The Quest of Kadji Lin Carter - The Man Who Loved Mars

Lin Carter - The Man Who Loved Mars Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria

Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria The Nemesis of Evil

The Nemesis of Evil H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos

H.P.Lovecraft: A Look Behind Cthulhu Mythos Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea

Lin Carter - Down to a Sunless Sea Horror Wears Blue

Horror Wears Blue Invisible Death

Invisible Death Lin Carter - The City Outside the World

Lin Carter - The City Outside the World The Volcano Ogre

The Volcano Ogre The Man Who Loved Mars

The Man Who Loved Mars